By: Nick Joseph

Cayman is a fascinating place to live. If you take the time, you can find yourself immersed in a distinct culture, and one that has been hewn in adversity by people from all over the world, coming together to create what we have today.

This article attempts to identify a few key elements of our past, and to emphasise some of the highlights (and lowlights), the echoes of which reverberate in the nuances evident in our society today.

What follows may be new to many of us. It differs, in some respects, from much of that we have been previously told, and it reminds us of the importance of raising questions.

In order to know who we are today, we must understand where we came from.

We have all been told of our “discovery” by Christopher Columbus on 10 May 1503. Ferdinand Columbus (Columbus’ son) recorded that they came in sight of two islands, “low on the horizon, and the sea about them was filled with turtles insomuch as they appeared to be small rocks”. They named the islands “Las Tortugas” (The Turtles) and continued their voyage.

Our history accordingly credits Columbus as our European discoverer.

He almost certainly was not.

It appears the first evidence we have of our Islands falling under European gaze came at least a year before Columbus – and the eyes were probably not Genoan, or even Spanish, but likely Portuguese.

The Cantino planisphere of 1502, a quite beautiful map of the world, depicts information gathered in the years prior to its creation and clearly shows Cuba, Hispaniola, and Jamaica. Off to the west of Jamaica, a group of islands (that can only be the Cayman Islands) is clearly portrayed. None of the (Cayman) islands are individually named but the area is called “The Antilles of the Crown of Castille” (my translation of the words “Las antilhas del Rey de caftella”).

Extract form the Cantino planisphere (1502), Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy. (Note Jamaica in blue – and a grouping of small islands to its west).

Today, the area is the Greater Antilles, which despite our relatively diminutive size, The Cayman Islands can claim to be part of.

The word “Antilles” comes from ancient times and was the name given to semi-mythical lands somewhere west of Europe in the Atlantic. There, as legend describes, Iberian Bishops (fleeing Muslim invaders from North Africa), are reputed to have found sanctuary.

Well, here we are. Sanctuary in a crazy world. Paradise found.

By 1523, the Turin World Map, widely considered to be one of the most accurate cartographic works of the Renaissance – look it up, it’s stunning! – referred to our islands as “Lagartos”, Spanish/Portuguese for lizards/alligators). Later, we would become known as Caimans. (Actually, on a 1597 map, Little Cayman and Cayman Brac were named the Caimanes, with Grand Cayman being named Caiman Grande. Later again, in 1608, Grand Cayman was recorded on a Dutch map as Caÿman Magnus.)

Notwithstanding our history, no one should treat this as permission to refer to us as “The Caymans”!

Caiman is the Spanish derivative of the Carib word “acayuman”, meaning alligator/crocodile. Caribs do not seem to have ever been here. The native peoples of this area were in fact an Arawak people – the Western Taino – and yet there is no clear evidence of them living here, despite their culture having pervaded Cuba, Jamaica and The Bahamas. They will have almost certainly visited.

In actual fact, the Dutch were the first known (albeit temporary) inhabitants of the Cayman Islands. They wrecked their ship, the Dolphijn in 1630. Those sailors were also our first shipbuilders. 122 crew survived for around 16 weeks while they built a replacement ship, which they named the Cayman. Upon its completion they successfully sailed towards Havana – abandoning the vessel when they encountered and were rescued by another ship near Western Cuba.

Francis Drake appears to have been the first Englishman known to set foot on Grand Cayman. He came with 23 ships in 1586, looked unsuccessfully for water, did battle with “crocadiles” and provisioned with turtle (which provided “verie goode meate”). This Elizabethan Sea Dog and his gallant men, of derring-do, with frilly collars, stayed for two days, then set fire to the island (ostensibly to deprive the Spanish of access to useful timber) and promptly left.

Our fondness for eating turtle (although now farmed) has endured. Within my life we still penned them in “Crawls” – a direct adaptation of the Dutch word “Kraal.” We also seem to be re-discovering our origins as the culinary capital of the Caribbean.

We continued as a stopping off point for the provisioning of ships of many nations, and of course, although later, of those flying the “black flag.” We were frequented by Dutch, French, Portuguese, and Spanish, as well as the English. Commerce developed to supply the transient vessels – first with turtle and later with pork (perhaps the original duty-free product available to people on visiting ships in the namesake Hogsty Bay). Ships were frequently careened in the area of Duck Pond, which had an adjoining Turtle Crawl.

Oliver Cromwell’s “Western Design”, sought to end Spanish dominance in the West Indies. In May 1655, his army, following a failed attack on Hispaniola, captured Jamaica. Many of the Spanish colonists hid or fled. Their slaves escaped into the mountains and formed the community which fused with the few remnants of Taino and became known as the Maroons. They were never defeated.

A number amongst those earliest colonists were Jews, who themselves were escaping the Spanish Inquisition. Descendants of those original Spanish colonists, and the original Maroons, are amongst the inhabitants of Cayman today.

In the late 1650’s, one of Cromwell’s sons arranged for the kidnapping and otherwise forced removal of thousands of Irish, together with some Scots and others, from their homelands and brought them to Jamaica in order to populate the island and enjoy the benefits of free labour.

Following Francis Drake, the second British people known to be in Grand Cayman were the antecedents of “Old Isaac” Bawden. Isaac, and a widow from Cayman named Sarah Lamar, are recorded as having been formally married in Port Royal Jamaica on November 9, 1735. They are understood to have founded the Bodden clan. At the time of Isaac’s marriage to Sarah (indeed, on the same day) the couple registered the births of two sons, Benjamin Lock Bawden (born 17 December 1730) and William Price Bawden (born 11 November 1732). The first known “born Caymanians?” Benjie and Billie?

Perhaps not.

Isaac was himself the grandson of the first actual Bodden (or Boden or Bawden) to settle in Cayman. Isaac’s grandfather is believed to have been one of Cromwell’s soldiers who captured Jamaica from the “Spaniards” in 1655. His first name may have been lost to history (as are the details of the Watler (or Walter or Walters) who accompanied him to Grand Cayman from Jamaica in around 1658). That original Bodden may be that original immigrant’s son, who was to be Isaac’s father. Isaac’s father may (or may not) have been born in Cayman.

Of course, for anyone to have been born, women need to have been intimately involved. Sadly, history seemingly does not accord those women the recognition they deserve and the names of any who came before Sarah Lamar, maybe lost.

Our relationship with the “Spaniards” was not good. This was not surprising. Oliver Cromwell’s army had indeed come to the region with the stated aim of dispossessing the Spanish of some of their territories.

Raids by Spanish forces from Cuba, on the sparsely populated and poorly defended Cayman Islands, were frequent. On 14 April 1669, a Portuguese “privateer” in Spanish service, Manuel Ribeiro Pardal, conducted a successful raid on Little Cayman, then probably the most populous of the Cayman Islands. He landed some 200 men, and reportedly burned some 20 dwellings to the ground. Several turtle sloops were also destroyed by fire.

There was plainly a penchant for burning stuff in the early days. Royal instructions were received by the Governor of Jamaica in 1662 to build fortifications in Cayman – and the resulting Fort George was eventually built in 1790, at what is today the end of Fort Street in George Town.

Piracy continued in our area. None other than Edward Teach, Blackbeard himself, captured a “small turtler” in Grand Cayman in the spring of 1718. Accompanying him was Israel Hands, as master of the newly captured 10-gun log-cutting sloop, “Adventure.” Hands, who was later shot in the knee by Blackbeard, was immortalised as a character in Robert Louis Stephenson’s 1883 classic, Treasure Island.

By the dawn of the Nineteenth Century, Little Cayman and Cayman Brac seem to have been abandoned and left without any permanent population.

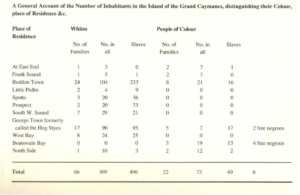

As we approach the first formal recognition of Emancipation Day in 70 years, we must also note that in the 1802 census, of the 933 residents of Grand Cayman, 545 enslaved people are recorded. Amongst them will likely have been a heroic woman named Long Celia. I do not know enough about her – but in 1820 she overheard some slave owners discussing the potential for the slaves being freed. What would long overdue European objections to slavery matter (the British having finally outlawed the transatlantic trade in 1807), if no-one told the slaves? Celia did. In Bodden Town, in a public place and following her conviction for stirring up rebellion and sedition, Celia paid the price with 50 lashes.

We should all remember Long Celia and commemorate her far better than we do.

By the 1802 census, not every person of African ancestry in Cayman was a slave, and not every slave owner in Cayman was white. Indeed, the census indicates that of the 545 slaves recorded, 49 were owned by persons “of colour”.

Some of the slaves in Cayman seem to have been brought from Central America. Certainly, in 1776, seven “Sambu Indians”, an ethnic group now known as the Miskito and who are of mixed African and indigenous American ancestry, were taken from the Mosquito Coast of Central America and sold in Grand Cayman. The Miskito people were enraged and held the British responsible. To ensure peace and effectively avoid a war, the British sent HMS Porcupine to Cayman to ensure the release of the seven. Later, in 1805, another Miskito in Cayman (and who it seems would have been recorded as a slave in the 1802 census) successfully petitioned for her freedom, and that of her two children – relying on the fact that under Jamaican law, all descendants of Indians from 1741 had been declared free.

This all adds to the nuance, to the complexion, and to the complexity of the Caymanian people and their history. “Mix up mix up”, as we say.

Details of our 1802 Census from Our Islands’ Past – a joint publication of the Cayman Islands National Archive and Cayman Free Press.

The circumstances of the taking and later freeing of the aforementioned seven became known as the “Sambu Indians Affair”. That “the lawless Caymanas” was ungoverned and seemingly accountable to no central power, had risked an important political alliance between the British and the Miskito. This directly contributed to the British determining that we needed to be treated as a dependency of (the colony of) Jamaica in order to help ensure that there was some jurisdiction to which we were “amenable”.

We seem to have long struggled with rules generally, and in particular those relating to immigration. The language of the British Commissioned Corbet Report of 1802 weaves a magnificent tale of the rule of law in the Cayman Islands at the start of the 19th Century. It describes as follows:

“The only laws or regulations in force they consider to be those of Jamaica, to the extent they are acquainted with them. They have no particular police. The magistrates are understood to have the same power as those in Jamaica – when any new measure is to be adopted, it is generally submitted by them to the consideration of the inhabitants at large. An “ill disposed” individual may give some trouble, and one of this description was lately shipped off the island to America, by the United Voice, by compulsion of the inhabitants.”

Imagine – 225 years ago, getting “voted off” the island! How embarrassing. It seems that the earliest Caymanians adopted firm immigration policies and were even able to achieve consensus as to what they should be!

It is also worthy of note that of 88 households recorded in the 1802 census, 15 were listed as headed by a Bodden. Whether he himself is regarded as a first or third generation Caymanian, Old Isaac certainly left his mark.

The Bodden’s seem to have come (whether willingly or not) from the southwestern peninsula of England. As do Patties (there, minus the spices) called Pasties, and Heavy Cake (there, minus the cassava) called Hevva Cake.

Long Celia, as with most people recorded in the 1802 census, was probably born in Cayman. Her people were taken from Western Africa. As were the Ackee tree (and fruit), and Anansi stories – an Ashanti equivalent of Aesop’s Fables – and on which many children in the Cayman Islands are raised to this day. I am myself privileged to have been raised with words of wisdom and morality from a trickster spider, as communicated by a wonderful carer from Jamaica.

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act came into force on 1 August 1834. We cannot celebrate that date as the end of slavery because, as is too often the case, we invent more flexibility in the application of legislation than the legislators anticipated. The British eventually had to land soldiers here on 3 May 1835 to guarantee the end of slavery once and for all. That is why we celebrate this important inflection point in our history in May, some 10 months “after the fact.”

Better late than never. I can only hope that Long Celia witnessed it.

This May, for the first time in my lifetime, we formally recognise Emancipation Day, on May 6, in addition to celebrating our perceived “Discovery” – this year, on May 20.

In 1992, 500 years following Columbus’ “discovery” of the Americas (which he had in fact believed to be India, and which in 1492 was already populated by an estimated 60 million people!), and 495 years following Columbus’ sighting of the Sister Islands, I was working for a short period in Little Cayman. The population was, as I recall, less than 30. Wayne Smith, a displaced Floridian, and I had been taking tourists fishing. We spied something strange on the horizon. Little Cayman District Commissioner, Bruce Eldemire, saw it as well. Our boats headed towards it – with Bruce arriving shortly before us. It was an unmotorised raft, hewn together with logs and bamboo. On board were two Germans.

Christina Haverkamp and Rudiger Nehberg had crossed the Atlantic, largely adrift, to draw attention to the continuing oppression of Yanomami and other indigenous peoples of the Americas, and the destruction of its rainforests. They had first crossed from Dakar in Senegal to Fortaleza Brazil. From there they set off for the United States – stumbling into Little Cayman. They were in a weakened state and had been harassed by persons who they described as pirates in the week before being “rescued.” They had a shotgun, which Mr. Eldemire promptly took into custody. (Rudiger later shared with me that his sight of the small Union Jack in the corner of the Cayman flag flying on Mr. Eldemire’s boat, may have saved the District Commissioner’s life).

Rudy and Christina were seeking to make a simple point at a time when the world was celebrating the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ “achievement”. If they could cross the Atlantic with a simple raft, why was the world stopping to laud Columbus? He had the backing of the Spanish Crown, multiple navigable ships, and technology. Even leaving aside the horrors that followed for the indigenous people of the Americas after Columbus’ arrival – including disease, genocide, and slavery – his voyages may not have been worthy of such widespread and significant celebration.

With the help of the people of Little Cayman (and, I believe, Thompson Shipping), Rudy and Christina ultimately made it (with their raft), to Washington DC and pleaded their case in front of the White House. Few braver people have I ever met.

Image – the raft in front of the White House – credit https://www.yanomami-hilfe.de/en/campaigns-and-projects/bamboo-raft-trip-1992/

I do not know if Rudy and Christina were right. They certainly caused me pause for thought.

“The Spaniards” were not the last to raid Little Cayman. Five youths from Grand Cayman share that distinction. On a Tuesday afternoon in November 2013, they landed in two boats. I recall reports suggesting some were dressed as Ninja’s. They tried to rob the very small Cayman National Bank office in Blossom Village, but omitted to note the bank was closed on Tuesdays, or the implications of the police having a helicopter. The RCIP intercepted the youthful miscreants on their return journey to Grand Cayman.

Nor were Pardal (or Blackbeard) the last known pirates (or privateers, or buccaneers) to operate in Cayman waters. That distinction seems to have been afforded to Gideon Ebanks. In 1933, he led a failed attack on a passing Cuban ship. It did not end well for Gideon. His body is understood to have been later found in the mangroves, where he was hiding out.

Fort George, built to defend against Spanish raiders, was ultimately destroyed, not in a raid by Spaniards, but by Cayman’s first National Hero, James (“Jim”) Manoah Bodden, on 11 January 1972, following, of all things, a planning dispute. Mr. Jim (who contributed much but was not perfect) got a statue.

There is no statue commemorating Long Celia…yet.

All of this, and so much more, is part of Cayman’s history. Founded on the seas. It is complicated. It is imperfect. It is discovered and lost, written and re-written. It sometimes differs, materially, from that which we have been told.

Whichever version we subscribe to, it is clear: Not everyone who comes here means us well. Not everyone who comes here comes because they want to. Not everyone that comes here will stay – whether we want them to or not. Not everyone that comes here will leave – whether we want them to or not. All impact us, and every impact causes reverberation and echoes. They develop the rhythm to which we march.

The bizarre facts are thus: We are (put bluntly) a colony, and yet were never colonised. The Dutch, English, Irish, Welsh, Scotts, Taino, Akan, Ashanti, Yoruba, Ibo and Ibibo, Miskito, Portuguese and Spaniards, and press-ganged assorted scallywags and indentured servants of many (and of no) nations, have fused to make us who we are. Many others now join us on the journey to who we will be.

Some were pulled. Others were pushed.

More will come.

Who they are, and where they will take us, rests in our hands.

*******

Note to reader: I encourage everyone who lives here to dig a little into the past and discover more. The National Museum, and National Archives are wonderful resources, as is the local history and culture course available to applicants for Permanent Residence and taught through UCCI.

Some of the texts from which much of our fascinating story can be gleaned (and which persons preparing to take the Permanent Residence Points System History/Culture test are encouraged to read) include:

- Bodden, J.A., The Cayman Islands in Transition: The Politics, History and Sociology of a Changing Society (ISBN-13:978-9766373221)

- Craton, Michael and the New History Committee (2003): Founded Upon the Seas: A History of the Cayman Islands and Their People (Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, ISBN-10:0972935835); and

- Kieran, Brian: The Lawless Caymanas – A Story of Slavery, Freedom and The West India Regiment (ISBN 9768012900)

Further reading which may be of interest includes A Brief History of The Cayman Islands, by David Wells of the West India Committee for the Government of the Cayman Islands.