By: Nick Joseph

Our economy, or at least aspects of it, operates on cheap labour. Wages are sometimes derisory and do not reflect basic economic principles where — other things equal — shortage drives up price. Wages, in some cases, are purely an artificial construct founded upon a nearly unlimited supply of labour. Much of that “minimum wage” labour comes to Cayman not only attracted by the relative opportunity our Islands present but sometimes driven by sheer desperation from their circumstances (and those of their families) at home.

If any employer can access almost unlimited high-quality labour (from every corner of the globe) at CI$6.00/hour, then no matter how skilled or experienced a Caymanian is, the salary level has been set. From this cursory perspective, it makes good business sense. Why pay more than absolutely necessary?

However, the social and economic consequences for a society are far less attractive. A Caymanian often must care for young children or an elderly parent. It is pointless to allocate responsibility to another person if, in consequence, they must pay that employee as many dollars for the care they provide as the caregiver’s employer can generate by working. It makes more sense to remain at home, provide the care, and sit out any opportunity for employment.

Our natural desire to employ the best people at the lowest possible rate has turned around and bitten us. It has driven down the value of our own labour, particularly in “less skilled” and entry-level positions — but the impact is spreading. Professionals are amongst those now seeing lower incomes than were previously available, especially if adjusted for inflation.

Some businesses (some of them very well-connected) rely not on particular entrepreneurial skills and expertise but on the margin between what they can effectively “rent an employee out for” and what they pay them. Of course, this can benefit businesses and the wider economy, but unregulated can be disastrous for the employment of Caymanians and our fragile middle class.

I do not subscribe to the rhetoric that “Caymanians do not want these jobs” or that “Caymanians consider certain roles beneath them”. It is offensive to suggest this to the grandchildren of persons who scrubbed the floors of hotel rooms with a hand brush, toiled across the globe in the innards of early 20th century ships, or cut bush armed with no more than a cutlass and their bare hands. It is an affront to a whole people to imply they are inherently not willing to serve drinks to tourists, bend steel or fix air conditioners.

This strikes me as a story told by addicts (addicted to cheap foreign labour) to explain their conduct. Sadly, it seems some of our own regulators may have been willing to subscribe to this deeply flawed perspective.

I hope it helps them to sleep at night.

My perceptions as to much of what is happening keep me awake. Many of the jobs filled by readily available foreign workers are entry-level positions, filled elsewhere around the world by young persons (often teenagers) trying to supplement any pocket money they are lucky enough to get or as the means of entering onto the job ladder.

Our youth are, however, forced to compete on (effectively) equal terms with skilled, experienced and artificially cheap labour at even the lowest rungs. With other barriers, including perceived inadequacies in aspects of our education system and struggling family units, are we setting the next generation up to fail?

We have created many unintended barriers to the employment of Caymanians, well beyond potential inadequacies of remuneration. The hand we have dealt to many of our own people presents significant challenges. Some of these are described below.

Inadequate incentive to upskill, work hard, and seek promotion.

In some businesses, there can be literally no material benefit to working hard and trying to get “extra hours”. Time and a half “overtime” pay is unavailable. Even if the employer abides by all the rules (and too many, regrettably, do not), the surplus of available labour is such that astute employers simply bring in “extra staff” for particular jobs to seek to ensure that profit-eating overtime pay never arises.

Without the ability to earn “extra” by going above and beyond, the whole relationship between effort and reward is destroyed. There is no means for even the hardest workers in such an enterprise to extract themselves out of subsistence-level pay. Keeping some of our hardest workers in a spiral of dependence is dangerous. It betrays the very principles of capitalism. Effort should (indeed must) be related to reward in any free market system.

Then there is another issue. The Department of WORC has struggled to curtail what likely amounts to abuses.

The difference in pay scales between the most junior and most experienced positions is sometimes too small. In an extreme example, a business may “advertise”:

WORC (like the Department of Immigration before it) has too often noted that no qualified Caymanians applied (of course no Caymanian applied!) and grants the permits.

This basic example shows how it can be pointless to work hard and “advance”. Extra work and responsibility entail zero increase in remuneration or benefits. In some circumstances, highly capable people refuse promotion to management because the operation of aspects of our labour laws (and particularly the exclusion of managerial level staff from the gratuities scheme) means that managers often take home less than those reporting to them.

For decades, our laws have had mechanisms to prevent much of this. The Immigration (Transition) Act (2022 Revision) s. 58(3)(d) says that the authorities considering the grant of a work permit shall (and with respect to a renewal, may) consider “the sufficiency of the resources or the proposed salary of the worker… and that person’s ability to adequately maintain that person’s dependants”.

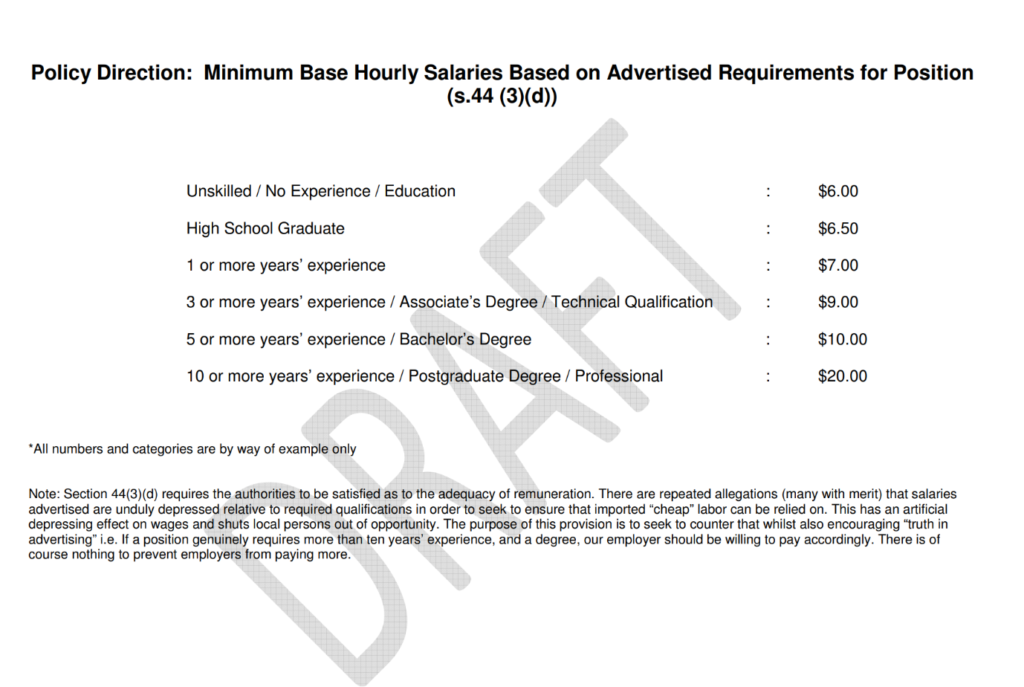

s.58(3) d was formerly known as s. 44(3)(d). After I first identified the problem more than ten years ago, I proposed the approach set out below to the responsible authorities at the then Department of Immigration as an attempt to abate the potential for artificially low salaries, including for the most skilled and qualified, from undermining the local employment market. Unfortunately, I never heard back.

Cabinet could literally issue policy directions along the lines of the above to the Department of WORC (separate and distinct from minimum wage, and more scientifically determined and data-driven than my “off the cuff” proposals) and this aspect of the problem would be (largely) solved.

The pension barrier to employing Caymanians and permanent residents

The principles underpinning Cayman’s Pensions Regime are sound. Allowed to operate as intended and designed, and given the required time to perform, it would do a fair job at alleviating some of the financial pressures on older persons, their families and the government in retirees’ later years. Anyone who employs a Caymanian or Permanent Resident must, from the first paycheck, deduct 5% from their pay and add an additional 5%, which must be contributed (up to the current cap on pensionable earnings).

This means that someone earning $100 will, in fact, “take home” $95 while costing their employer $105. The $10 difference will accrue in the employee’s pension account.

Fair enough — insofar as the intention is to provide workers with some measure of future security whilst also allaying the government’s future liabilities and obligations.

But then we exempt expatriates from any participation in the pension regime for their first nine months residing in the Islands. This means that (for their first nine months of employment) a newly-arrived expatriate earning $100 will cost their employer $100 and take home $100.

Their Caymanian colleague, employed in the same role and starting on the same day, will take home $95 and cost their employer $105. It is, therefore, 5% more expensive to employ a Caymanian over a foreign national in the same role and with the same conditions of employment. The Caymanian will have $5 less in hand to meet the same cost of groceries faced by their expatriate colleague.

Some may argue that this is offset by work permit fees, but with work permit fees as low as $0 (for those employed by a church, a school, or a charity), $300 for a transport-helper and porter or packer, car tinter, dish-washer or car or boat cleaner, $375 for a gardener or janitor, $500 for a kitchen helper or doorman, and $550 for a labourer, expatriate workers can nonetheless be cheaper to employ than locals.

It becomes starkly evident when pension exemptions are multiplied. Across 50 new staff being paid $2,000/month, in nine months, the payroll difference (equating to savings for the employer) makes it $45,000 cheaper to employ foreigners than Caymanians. This amounts to state-sponsored incentivisation to employ expatriates over Caymanians of almost $1,000/person.

To level the playing field, a simple fix would be to change the pension obligation to “everyone employed for more than three months”, effectively stopping any direct economic incentive in favour of employing foreign labour over local workers.

Exclusion from bank financing of some service industry and commission-based workers

In the service industry in particular, there is another longstanding issue that is displacing Caymanians from appropriate participation. Some financial institutions (like the Department of WORC in processing PR applications) will not give full credit for the gratuities/tips elements of wages or commissions.

This means that if workers are seeking financing, even though the job may pay well, only the guaranteed base pay of $6.00/hour (and not the additional $20.00/hour that may be available through tips and gratuities) is taken into account. This can mean that workers are excluded from financing and cannot get a car loan, student loan, or mortgage through regular channels.

In egregious cases, I have seen Caymanians leave well-paying jobs in tourism to get a less-paid office job — not because they did not like the hours, working hard or serving foreigners. On the contrary, even having saved sufficient funds for a down payment/deposit, this is the only route by which they can obtain the financing required to (finally) buy their own home.

The takeaway: it is maths that has been contributing to Caymanians not participating as fully as they once did, and still might, in the tourism sector. Not the more often ascribed laziness, ignorance or pride.

Turning a “blind eye” to substandard housing

Of course, foreign labour can survive and even thrive on salaries below those capable of sustaining many of their local counterparts. How? By sharing accommodation, sometimes at levels far far below those expected by planning regulations. Bunk beds in a single bedroom, so that each can house four unrelated adults, is one way the cost of living has been addressed.

Stories even exist of shift workers sharing the same beds — hot bunking — so in fact eight (or more) workers can share a single 4-bunk bedroom. Shipping containers have been proffered to some foreign workers.

Cayman becomes much more affordable — with sacrifice — if several people split the electricity bill and cook communal meals. This lifestyle is unavailable to a single parent or person responsible for the care of an older relative. It appears impossible if our laws are being properly and consistently applied.

Unequal application of labour protections

We have inadequate “whistleblower” or other employment protections. All too frequently, raising a complaint if you are a foreign national on a work permit results in little more than a cancellation of your work permit and a ticket home (at your own expense).

Pursuing a labour complaint from overseas while unemployed, and all for a whole two weeks’ base wages for each completed year of service (and nothing if you worked for less than a year) is unworkable. It is made worse by the fact that complaints can take years to conclude — and some employers can simply move on with a work permit granted in favour of their next employee. If only we had implemented a long-anticipated “accreditation system” as part of our work permit regime.

Of course, the law seems to operate better to protect Caymanian workers from unscrupulous employers — but therein lies the problem. Caymanians know who is who and do not apply for the jobs, and what unscrupulous employer would employ them anyway if the result will be shared in the morning on Cayman Marl Road — seemingly the ultimate enforcer of many of our laws and standards?

Truth in advertising

Very well-paying jobs are often “advertised” as $6.00/hour + Gratuities. That does not “look” very attractive to persons already earning $30,000 a year. However, these roles can and do often pay in excess of $60,000/year. Jobseekers are unaware, and so they neither apply nor seek to obtain the requisite skills and experience required for such roles.

The fix is simple: Require the fullest disclosures of expected remuneration (including tips, gratuities, school fees, housing, vehicles, airfares, etc.). Too often, this has been withheld from potential local jobseekers and from regulators who should be demanding this information.

The (sometimes shocking) reality of reduced hours

Tourism has seasons. In December (as we can see from a marked increase in traffic) through April we are hopping. Thousands of tourists come and enjoy all that Cayman (bolstered by exceptional hotels and culinary establishments) has to offer during this “high season”. An enterprise may require 200 workers (all working 40-hour weeks and participating in a waterfall of gratuities).

The same enterprise, in the September, October, and November “quiet season”, may only need 50 staff. Gratuities become limited as establishments cut their rates (sometimes to zero for the right influencers) and more cost-conscious customers avail themselves of the services. No mind. The solution of some enterprises is to reduce hours across the board for all staff. Ten hours a week is all that it takes to get the job done.

The problem herein is that employees (with not only reduced hours but also greatly reduced gratuities) face less than 25% of their income while continuing to face 100% of the cost of living in one of the earth’s most expensive places. In fact, with the heat of the late summer, the period of greatly reduced income corresponds with the highest electricity bills.

Young North Americans employed in the service industry ameliorate the problem. Some of them can (and do) voluntarily take unpaid leave and surrender their shared Cayman lease (but not their work permit). They can return “home” and live inexpensively. Some can even head for an idyllic cottage by a lake, living inexpensively and seeing family and friends for a couple of months. They can then return to their job in Cayman when their income can again be sufficient to allay the realities of our high cost of living.

For most Caymanians, this is emphatically not an option. They must bear the costs year-round, whether their income makes it affordable or not. Then we add insult to injury. If you have a local family (a condition much more likely to affect a local person than a “young, free, and single” expatriate tourism worker), then your employer must, in some circumstances, deduct the cost of your dependent’s health insurance from your paycheck. With hours reduced and gratuities curtailed, this can result in negative remuneration.

I will never forget the look on the face of a young woman some years ago. Cheeks stained by tears, she trembled as she passed me her pay- slip. After deductions, it had turned negative. Then came the real sting from the hardworking, freshly minted Caymanian single mother (of African descent):

“When there was slavery, there was no pay. Today, I end the month owing my employer money. How can that be?”

This is not a problem of the health insurance system. Largely, it results from the lack of use of (or imposition of) seasonal permits and our permissive attitude to cutting hours (and remuneration) to a fraction of those expected for full-time employees. The answer, as is the case for much that ails us, is in our Immigration (Transition) Act. We should understand it and apply it.

The childcare dilemma

A single mother without a reliable family network to rely on and an absent father (too often and too easily able to avoid the obligations in his role, however fleeting) needs childcare to be able to work. Unless the child is of school age, and even then, during the school holidays (or unexpected weather closure), she must pay for it herself.

If a mother is to leave her child in the care of a paid carer, that carer will have to be available to care for the child from the moment the mother leaves for work. If the mother faces a one-hour commute and works an 8-hour day, she will have to be away from her child for 10 hours. If our laws are being followed, the mother earning minimum wage will earn CI$45.60 for her day’s work — $6.00 x 8 – 5% (pension).

Meanwhile, the helper will have to be paid CI$63 ($6.00 x 9 plus 1 x $9 (time-and-a-half overtime for the tenth hour). Adding the cost of the carer’s health insurance, the cost to the mother will be around CI$73.00.

It follows that a mother will literally be CI$27.40 richer every day if she sits on the couch with her child rather than going to work – and that is even without considering the costs of transportation to and from work or the impact of inadequate care.

Part of the answer may be found in a system of government (and even employer) subsidised daycare and effective, reliable transport (further below).

The currency of remuneration

Small change, perhaps, but many employers pay salaries in United States dollars. This makes sense. Although they do not hesitate to price their products and services in Cayman Islands dollars and enjoy a multi-percent conversion spread, their revenue is generated in US dollars, and for larger operators in particular, their expenses are often in United States dollars. Their expatriate employees often prefer to be compensated in United States dollars.

But their Caymanian employees operate in a Cayman dollar environment. Their expenses and day-to-day living costs are met with dollar bills and debit cards in smaller increments. If their revenue is in US dollars, but their expenses are in CI dollars, they lose a couple of percent on every transaction. For those struggling to make ends meet, this becomes yet another burden.

The public transport barrier to Caymanian employment

A lack of reliable public transport also serves to exclude Caymanians from jobs. Expatriate workers are not impacted to the same extent. They can choose (or be assisted with selecting) housing in relative proximity to their workplace and live in communion with others (seemingly often in breach of planning and development regulations). They can share costs and, for example, transport.

These options are not available to a Caymanian who may literally have been born into the place they live — and must account for housing for children and/or an elderly parent they must care for.

A key component of any job is the ability to turn up on time and be ready for work. If and when a worker cannot reliably and consistently be punctual in arriving at their location of employment, any employment relationship will be necessarily short-lived.

JobsCayman

Does it WORC work? No. And it never did. Its recent replacement continues to present challenges. The problem does not lie with the department’s hard-working civil servants. Instead, it has emanated from a seemingly simple change.

If the intention of getting rid of newspaper advertising was to penalise elements of a supposedly “free” press for drawing certain adverse inferences, mission accomplished!

If it is to test the job market and draw opportunities to the attention of prospective local candidates, not so much. Although it may be a work in progress, it seemingly has a long way to go before it can rival the effectiveness, accessibility and efficiency of newspaper advertising, which worked not only to introduce the unemployed to jobs but, as importantly, alerted the already employed to opportunities for upward mobility or increased job satisfaction.

Artificially low work permit fees and a potentially undermined apprenticeship system

Work permit fees are more than a means to generate revenue or to offset the cost of administration. They also serve to act as a disincentive to employ foreign labour that an employer does not actually really “need.” This is why the statute makes it an offence (frequently committed) for a worker to pay or contribute towards their own work permit fee.

For fifty years, it has been an expectation of our work permit regime that any time a skilled employee is needed, a genuine effort is made by that employer to equip local people with those skills. Apprenticeship enshrined in legislation.

Unfortunately, we seem to have forgotten that. Rather than emphasising the training and mentoring of local persons, we are now sometimes feeding industry with relatively unskilled foreign workers, in droves, for what effectively amounts to “trainee” positions.

Are these positions really what they purport to be, or are they simply a means of incurring the cheapest possible work permit fees? How we can ever expect to instill relevant skills in meaningful numbers Caymanians, if those same Caymanians must compete for training opportunity with almost all the entry level positions available to foreign labour at work permit fees of less than CI$1,000/year?

Washing the neighbour’s car, mowing the lawn, babysitting, construction labour or flipping burgers (the traditional step into the door of gainful employment for teenagers all around the world) is increasingly unavailable to local persons.

As of the end of last year, 1,020 expatriates were here on work permits as kitchen helpers (annual work permit fee CI$500), 270 as car cleaners (annual work permit fee CI$375), and 1,057 (annual work permit fee CI$375) as gardeners.

We should hope, given our rich nautical heritage, that we can at least get our kids experience as deckhands, right? Perhaps, but at the end of last year, they had to compete with 86 work permit holders (annual fee CI$500).

While unsung heroes like Michael Myles and his Inspire Cayman Training seek to ensure the provision of training and opportunity to local persons, we had, as of the end of last year, 74 apprentice plumbers on work permits (annual fee CI$875). Imagine, our systems may be facilitating, importing and subsidising the employment of foreign labour for the purpose of training it!

Is much of what I am suggesting inflationary?

Perhaps, but not necessarily. These are just ideas. I am throwing them out for debate and discussion. Each will have pros and cons. These thoughts are a product of more than 25 years working in “local practice”, often in the weeds with real people and real businesses, with real people and real problems.

Many of Cayman’s employers compete successfully and provide excellent service and a great standard of living for their workers, remunerating even entry-level positions at well above minimum wage, employing a large proportion of Caymanians and remaining highly profitable.

There is also an unfortunate reality. Others operate profitably only because they conduct their affairs at what may be politely described as “sub-optimal” levels. Our permissiveness (contrary to the intention of our laws) is necessarily resulting in a substantial importation of poverty.

Poverty needs to be subsidised by government (and/or the wider community). It makes people unable to support themselves. Government has to step in and provide support. That costs money. That money comes from fees and taxes. Those fees and taxes are (usually) inflationary.

Lowering fees and taxes is one way to ameliorate the cost of living.

There is also the reality that automation is part of the future. According to recent data, there were 679 expatriates employed as retail cashiers in the Cayman Islands. When we do what much of the world has already done and replace a couple of hundred of them with self-checkout and automatic payment technology, then the consequence is going to be less cash and fewer cashiers. Not good news for the cashiers but good news for most consumers… and for the availability of entry-level housing stock.

Less physical cash also means less security. And fewer security guards (735 as of the end of last year, on an annual work permit fee of CI$1,732.50).

And fewer people forced to live in poverty.

And less traffic.

Everything is linked.

The roof is on fire

You may now recognise that I have an affinity for song lyrics as a means of emphasising a point. It can perhaps act as a jingle in the minds of readers. This whole situation brings to my mind 1984’s Rock Master Scott & the Dynamic Three and their single, “The Roof is on Fire”.

Faced with a situation of the scent of smoke emanating from the soffits (as we may now have), we have a choice: Do we call the proverbial fire brigade and properly work across ministries with teams of bucket (rather than buck)-passing citizens uniting to understand and fix the issues?

Or, to put it bluntly, are we going to continue to sit, drunk on our addiction to cheap replaceable labour, and ultimately, filled with glee and mesmerised at the bright light and sparks emanating from the nascent inferno, begin to chant: “We don’t need no water, let the…“ (you probably know the rest).

However inelegantly, I just threw a bucket of water in the direction of some of the perceived hotspots. If others do as well, we just might be able to have a vibrant AND sustainable economy in which the Caymanian people, foreign workers, and employers, whether they be Caymanian or not, can thrive.